Every time you want to buy an item of expensive, vintage frippery there’s always an internal war between your possession-hungry heart yelling ‘yes’ and your stern Jiminy Cricket head urging ‘think of the gas bill’. My own heart v heart battle is seriously conflicted over my desire to own a set of Dionne Quintuplet dolls.

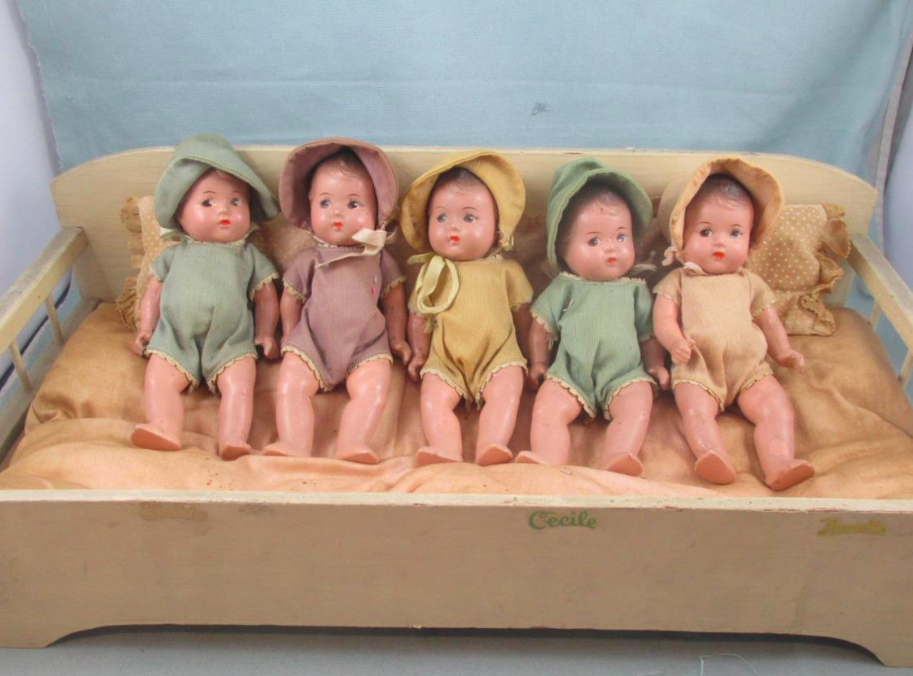

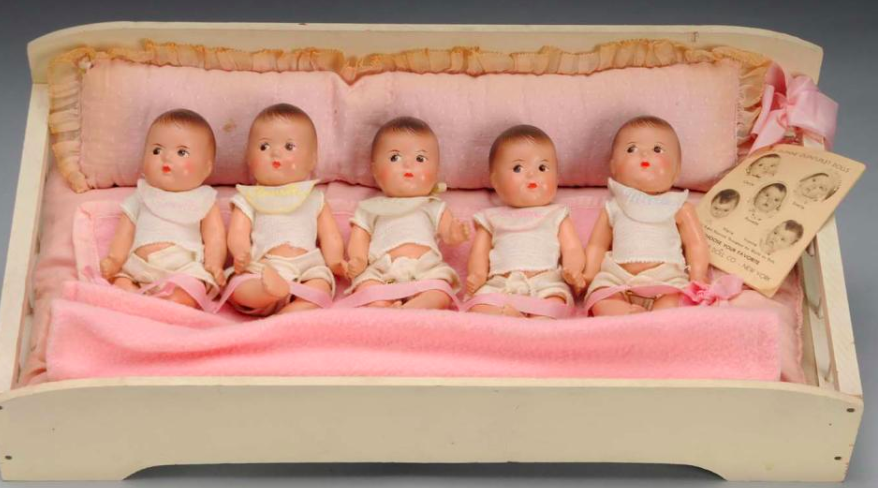

On the plus side, they are cutest dolls ever made. The best examples, made in the 1930s under licence by Madame Alexander, often have come with cuter accessories like named bibs cribs, bonnets – and nurses. On the unavoidable down-side, these dolls are a tangible reminder of the fact that five little girls – the real Dionne quintuplets on whom the dolls are based – were exploited by the very adults entrusted with their care. These harmless looking dollies were souvenirs of a shameful period of time when the girl’s parents, medics and even their country were keen to exploit the ‘greatest tourist attraction on the face of the globe.’

The Dionne quadruplet story began in the early hours of May 28, 1934. It was 4am when Elzire (along with husband Oliva Dionne) of Callander, Ontario in Canada, welcomed the first of their babies…midwife Madame Lebelle popped the tiny little ‘creature’ in her palm of her hand to warm the blue-tinged body before the oven. By the time Dr Allan Roy Dafoe arrived at the house, there were two babies on the bed and a third on the way. “Good God, woman,” he’s reported as saying “Put on some more hot water.”

When a fourth and a fifth appeared almost immediately the doctor was reduced to uttering ‘Gosh’.

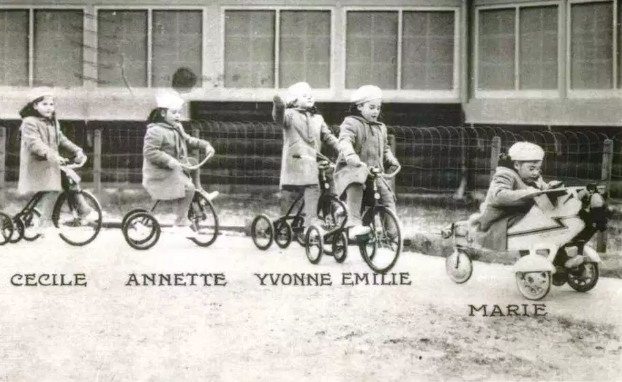

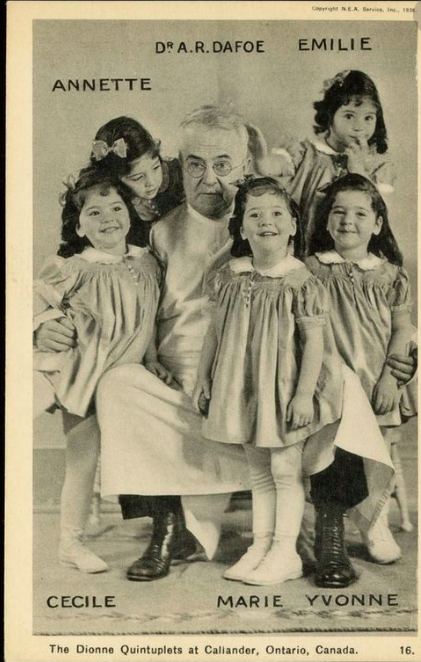

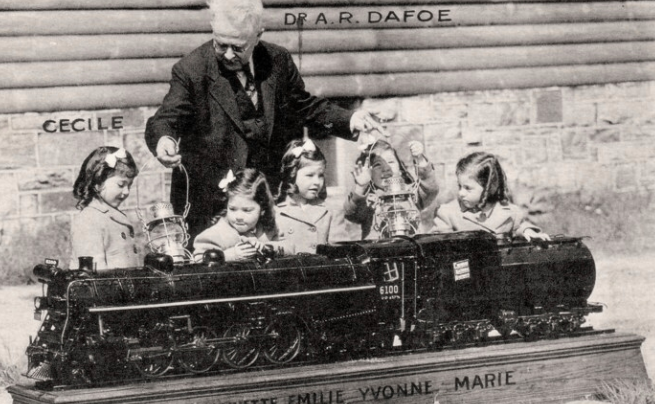

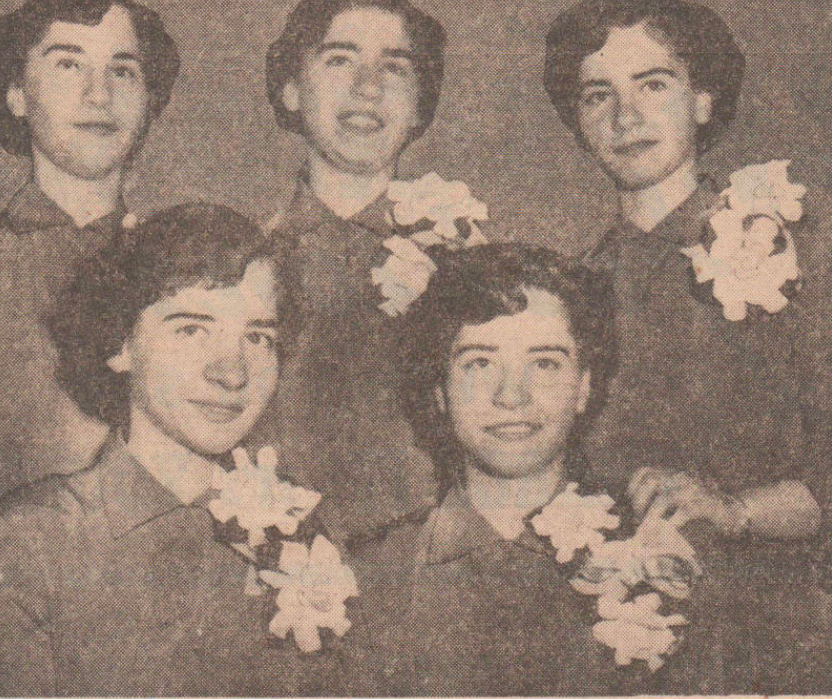

The five sisters – Annette, Cecile, Yvonne, Marie and Émilie – become known as the Dionne quintuplets. Together they weighed less than 14 pounds. The Dionnes were the world’s first, surviving, quintuplets born from a single egg.

According to a later account by Cecile, it took just 24 hours for the ‘circus’ began. At 4am the following morning, Dr Dafoe was roused from his bed by a call from a reporter in Chicago. Within hours, The Toronto Star had dispatched two reporters and a famous war vet’ photographer Fred Davis with a basket containing ‘six hot‐water bottles, six dozen diapers, ten small woollen shirts, five padded bonnets, five blankets, two dozen nursing bottles, 20 nipples and an oval bathtub’ – costing around $300; an eye-watering sum in 1934.

It was a sound investment. Davis became the official photographer and one of the reporters, Keith Munro, became their business manager. It also made a star of the doctor. Seven months after the Dionne quintuplet’s birth, Dr Dafoe was lauded as a celebrity when he arrived to give a 40 minute sell-out talk – with slides – to 3,000 at Carnegie Hall in New York. Their mother was to remark “Everybody but me is making money out of my babies,” (not true – the parents and their children – they had five more at home – were making stage appearances for cash in the Mid-West before the girl’s were a year old).

Regrettably, it was the impoverished father’s desire to make money from his daughters which led the Ontario Government to issue an enforced guardianship order. A hospital building – the ‘Dafoe Nursery’ was specially constructed across the road from the family farm-house under the control of the doctor and a team of nurses. The babies, who were two month premature, were frail. Two years on, Dr Dafoe was awarded custody of the children until their 18th birthday. By now, the girls were thriving and everyone wanted to see them.

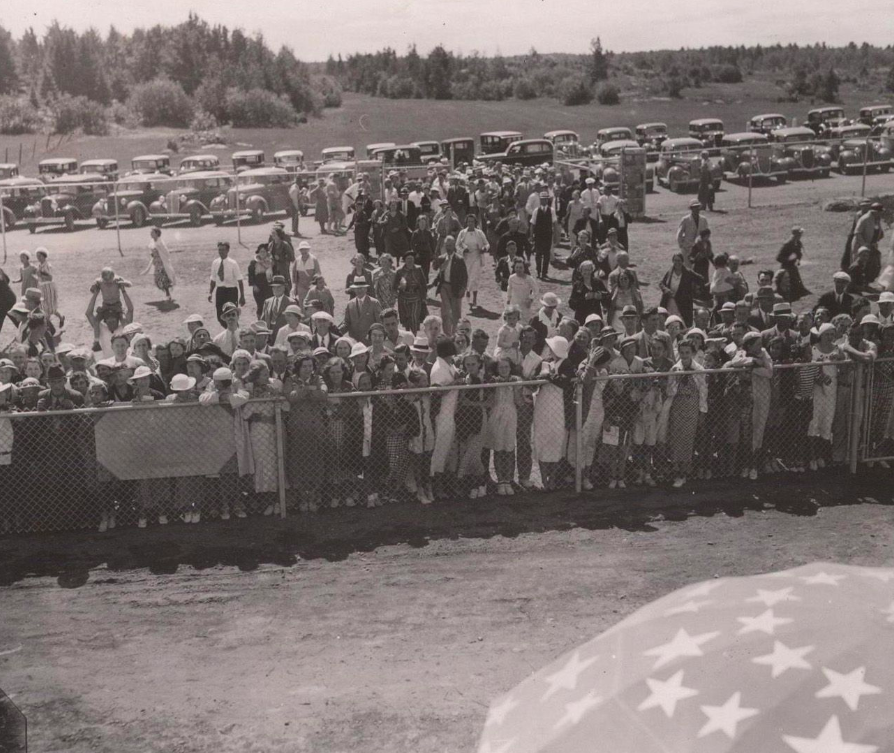

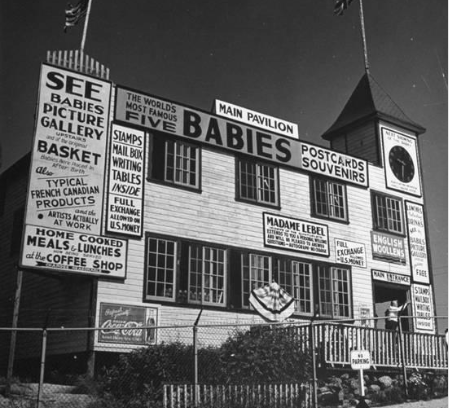

Ironically, while the Dionne sister were isolated from other children and their own parents – they were allowed to visit but the girls were two-years-old before they were permitted a brief play session with their brother – they were subject to the gaze of up to 6,000 visitors every day. Dafoe decided to open up the horse-shoe shaped playground and the girls were ‘exhibited’ behind screens two or three times a day. People would queue for hours for glimpses of the sisters before going off to buy souvenirs and soda. What started as a medical facility became little more than a theme park which became known as ‘Quintland’.

It’s estimated the government made half a billion dollars from the three million tourists who flocked to the viewing areas every day – it even eclipsed Niagara Falls as an attraction. Tourist leaflets were produced to entice people to the ‘spectacle’ of seeing five impossibly cute little girls in their orphanage-like habitat; ‘ “The whole family,” claimed the leaflets, “will be happy in Quintland this summer.” Meanwhile, the parents sold their autographs at 25c a pop (they couldn’t sell pictures as they couldn’t take any – all the image rights belonged to Fred Davis).

The government and tourist board weren’t the only ones cashing in on the so-called ‘quints’. They inspired movies, articles and their names – and that of Defoe – were linked to hundreds of advertisements.

“Before they were 3 years old, the quintuplets had endorsed every kind of product from Pure‐test cod‐liver oil and Musterole chest rub to Remington Rand typewriters,” writes Pierre Berton in bis seminal books The Dionne Years.

“They even received $300 in royalties from a song called “Quintuplets’ Lullaby,” which sold some 22,000 copies.”

The birth of the quintuplets even boosted trade in the area as every ma and pa shop sold momentoes bearing the girl’s likenesses including games, games, toys, books, calendars, postcards and plates.

Leslie Hardman, of the Chicago Tribune, says the memorabilia is still desirable. “All of these items are collected, but none are more desirable than your Madame Alexander quintuplet dolls,” he wrote in respond to a reader enquiry about the value of her own quintuplet dolls.

“As a girl, Madame Alexander (Beatrice Alexander Behrman)…first making dolls at her kitchen table and then moving to a studio in Manhattan. In the 1930s, she obtained exclusive rights to make dolls of Scarlett O’Hara, Princess Elizabeth and the Dionne quintuplets.”

Life within the compound was very different to that ordinarily associated with child celebrities. They were under the ‘guidance’ of child behaviourist Dr William Blatz. It was Blatz who designed the play area and devised a routine for the girls which saw them being sent to an isolation area (attached to their nursery) on signs of any unacceptable behaviour; like talking during meals.

According to Pierre Barton, one of the girls heard frogs croaking and suggested the nurse ‘put them in the little room for talking in their beds.’

In 1995, Cecile Dionne described the girl’s routine to Ian Parker of the Independent; ‘The whole thing was quite severe for babies and young children. Starting at six o’clock, until six o’clock at night, we had 21 items to accomplish. A time to go to the toilet, all of that. A time to eat, to play – and to meet one’s public.’

The girls couldn’t see the hundreds of people crammed behind the gauze walls but; ‘We saw moving. We heard sounds,’ Cecile recalls.

Other than an awareness of people, the girls hardly met anyone from the outside world. ‘We were a club, a society, a civilisation all our own,’ Cecile concluded.

When Elzire and Oliva finally succeeded in winning back custody of their children – their father Oliva and Defoe fought a bitter custody battle in the courts – they were nine-years-old.

As usual, the press were out in force to record the event.

“It’s lovely to have mamma and daddy always near,” Yvonne was quoted as saying. “I am so happy. It is just like the picture books; our new home is so nice.”

Sadly, the sister’s reunion with their parents was nothing like the fairy-tale happy homecoming described by the media. The girls had rarely seen their family and – according to later accounts – they were treated as little more than servants.

In 1995, three of the quintuplets instructed an author to write Secrets de Famille (available only in Canada). According to Ian Parker of the Independent, the book sets out details of alleged parental abuse.

“The new book…includes the charges that, following the Quints’ return to their parents – from Quintland in 1943, they were sexually harassed by their father, and beaten by their mother,” he writes.

“The father rubbed ointment into their breasts, liked to manufacture a crush of bodies in the car, made specific – unsuccessful – sexual advances. Their mother treated them like dirt. When the quintuplets reported their alarm to a local priest, they were given no help – rather, they were advised to wrap up.”

Ian questioned Cecile in 1995 about her father’s abuse and was told; ‘Dad asked me to be his mistress and I refused, so after that I didn’t have any bad things…”

With Yvonne he was more insistent: “He wanted her to go inside and to lie on the bed. But Yvonne didn’t want to go inside…” (she did not comply).

Years later, in their book ‘We Were Five’, Cecile Dionne wrote about her parent’s attitude towards them. “They behaved,” she wrote. “As though they were partners in some unspoken misdeed in bringing us into the world. We were drenched with a sense of having sinned from the hour of our birth. We were riddled with guilt.”

The parents clearly helped themselves to the girl’s trust fund – said to amount to a million dollars by 1940 – to buy a mansion house the girls’s called ‘The Big House’.

“It was the saddest home we have ever known,” Cecile concluded of the mansion.

Although the parents continued to encourage the girls to attend events to earn appearance fees, pubic interest in them slowly dwindled. Royalties from the exclusive photographs declined and the market for merchandise ground to a halt. But as public interest receded, all the quadruplets cared about was the absence of love from their family.

‘It’s tough to go on living when you feel that your family doesn’t love you. It’s difficult to live without love. It’s like a plant without water,’ Cecile told the Daily Mail in 2016.

The girls had to endure nine years under their parent’s care; working hard and being denied the luxuries enjoyed by their siblings. At the age of 18, their father sent ‘the quints’ to continue their studies at the convent of the Sisters of the Assumption at Nicolet, in Quebec. Emilie and Marie both decided to become nuns. Emilie, who moved to a convent near Montreal, died after suffering from an epileptic fit. She was just 20-years-old.

According to Cecile, Emilie’s death loosened them from the oppression of being the quintuplets. Yvonne and Cecile began nurse training. Marie left the convent and Annette started to study music. At 21, the girls were finally due to access to their trust funds – they had been living off the few dollars their father sent them of their own money.

Cecile married in 1957, Annette a month later and Marie the following year. All three marriages failed. Marie died alone – and undiscovered for three days – in 1970. According to the remaining sisters, Marie was a heavy drinker who ‘neglected herself’ and suffered a suspected blood clot on the brain. Relations between the girls and their parents were never restored. From the mid-50s until his death in 1979, the four girls saw him just five times. Their mother died in 1986. Cecile told the Independent’s Ian Parker she has no regrets because the parents refused to ‘admit that they were wrong’.

“We should have been raised like normal children,” she concluded.

In 1998 the three surviving sisters sued the Ontario government, seeking damages for the trauma caused by their unorthodox up-bringing and for a share of the revenue earned during their years under state care. They reached a settlement of four million Canadian dollars ($2.8million USD) and split it equally, one portion going to their late sister Marie’s children.

A final sad footnote to the quintuplet’s story concerns Cecile. With her health declining, she moved into a private care home with the fees being paid out of her bank account administered by her son Bertrand (the third of her four children and a twin whose brother died). In 2012, the payments stopped. Bertrand – and Cecile’s money – had disappeared. According to the Montreal Gazette, Cecile’s attempt to track him down have proved futile and she now lives on a government pension.

As of June 2018, there are two surviving sisters Cecile and Annette, Yvonne died in 2001. In their last public ‘appearance’ the three sisters wrote an open letter to the McCaughey septuplets born in 1997.

Dear Bobbi and Kenny,

If we emerge momentarily from the privacy we have sought all our adult lives, it is only to send a message to the McCaughey family. We three would like you to know we feel a natural affinity and tenderness for your children. We hope your children receive more respect than we did. Their fate should be no different from that of other children. Multiple births should not be confused with entertainment, nor should they be an opportunity to sell products.

Our lives have been ruined by the exploitation we suffered at the hands of the government of Ontario, our place of birth. We were displayed as a curiosity three times a day for millions of tourists. To this day we receive letters from all over the world. To all those who have expressed their support in light of the abuse we have endured, we say thank you. And to those who would seek to exploit the growing fame of these children, we say beware.

We sincerely hope a lesson will be learned from examining how our lives were forever altered by our childhood experience. If this letter changes the course of events for these newborns, then perhaps our lives will have served a higher purpose.

Sincerely, Annette, Cécile and Yvonne Dionne

So should you invest in Dionne quintuplet merchandise and products?

Is it possible to collect quintuplet related dolls, toys and merchandise once you’ve heard the Dionne sister condemn people who use children as an ‘opportunity to sell products’?

It’s a question I simply can’t answer. It’s done to the individual conscience. As a salve to anyone who does find themselves waning to own a bit of Dionne ‘history’ it’s worth recalling that the sisters are also grateful that publicity – and the merchandise – help to keep their experiences fresh in people’s minds; hopefully preventing future exploitation.

Looking at internet sales, it’s clear there is still a demand for Dionne memorabilia – there’s even been reproductions and special editions made in recent years. However, in common with most antique dolls, prices have taken a nose-dive in the last ten years. In March 2009, a full set of Dionne quintuplet babies, with name tags, sold for just $450 at auction (picture below). Ten years earlier the Chicago Tribune(see above) suggested similar dolls would fetch $600-1,200. Much of what is available on sites like eBay and Etsy are items imported from the US.

Here’s a guide to some June 2018 prices on eBay.

A rare set of 1930s quintuplets in original swing sold for an offer close to £904 on June 22.

Sources; The Dionne Years, Pierre Berton. Serialised in the New York Times

The Dark Side of the Famous Five by Ian Parker of the Independent

And for remarkable images www.quintland.com