It may seem an almost guilty confession these days but I loved Enid Blyton. The stories may seem narrow in their focus today but the world they evoked was exotically middle-class to a working class girl more likely to discover a magical world at the top of a Faraway Tree than get her chops around some ginger beer.

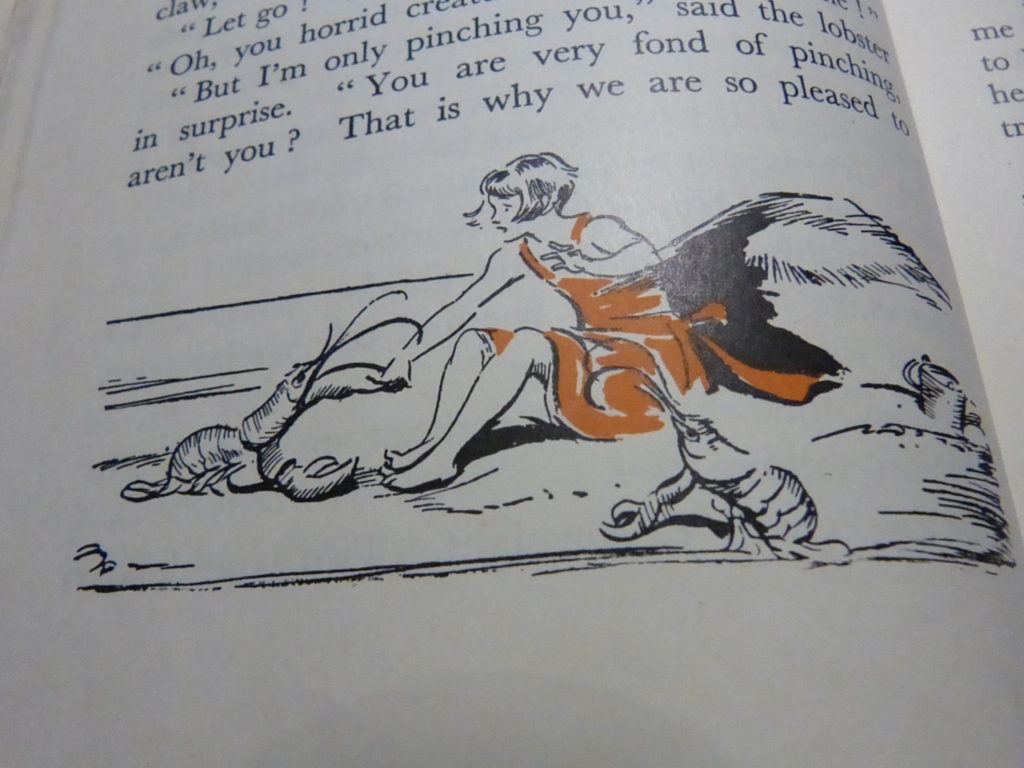

What added to the appeal were cast of the cherubic-faced children illustrated on the covers and lying fragrantly between the leaves. The antics of children with lashings of blonde locks, good cardigans and spiffing teeth were about as faraway from my early childhood as it is physically possible to get.

I hadn’t thought about magical world of Enid Blyton for years. Then I turned fifty. Hormones do funny things and I found myself filling my empty nest with comforting and nostalgic items from my childhood.

Which is why I came to bid an eye-watering amount of money for a box of vintage Enid Blyton classics when they came up at a local auction. When I collected the little treasures, I was about to drive away when a porter flagged me down and asked if I’d like help with the other eight.

‘Books?’ I asked secretly thinking I had quite enough books to satisfy my nostalgic cravings.

‘No, boxes,’ she smiled.

Very large boxes. Unwittingly, I may be the owner of one of the most impressive vintage children’s books in the country. My dog certainly thought so; I nearly had to hoof him out of the car to get the dratted things in the boot.

Lessons clearly not learned, I also went a little crazy for two very kitsch rabbit ornaments which came up at the next auction. One was a lop-eared Sylvac rabbit, the other a Hummel figurine of a boy and an orange rabbit which was standing in a green dish.

I didn’t pay the dish any heed until I came to list the Hummel figure for sale on Etsy and realised the boy and his stand were not a pair.

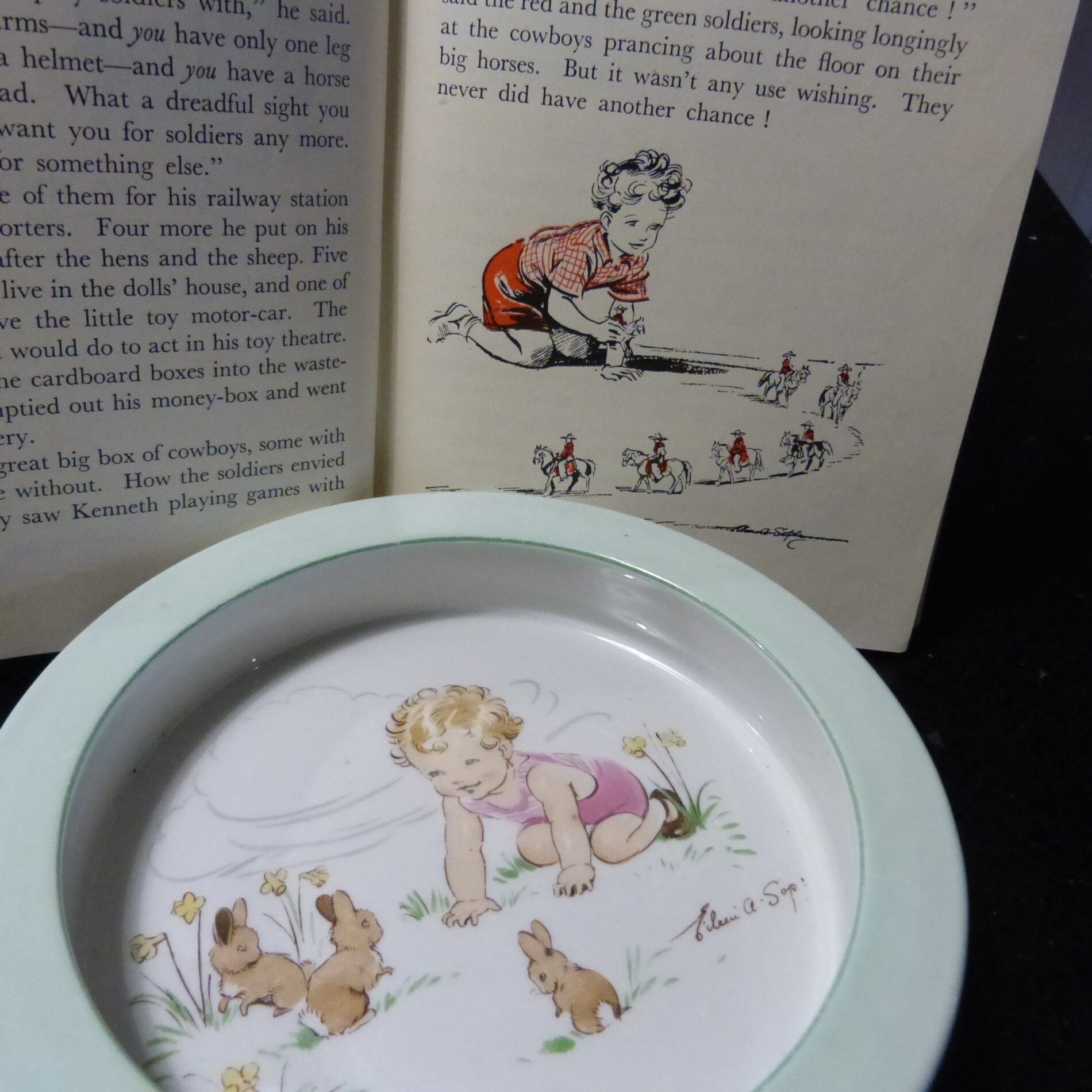

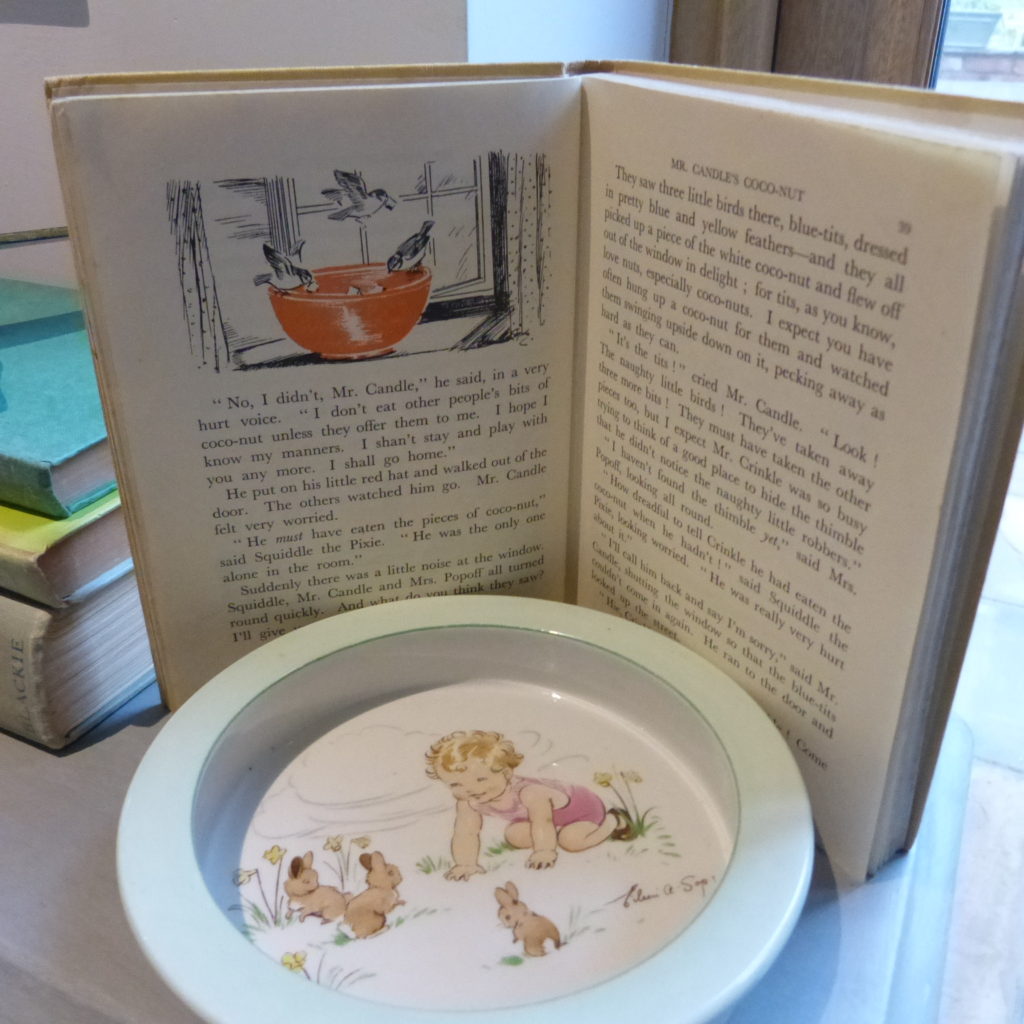

Thrillingly, the inside of the dish featured a delightful illustration of a little girl surrounded by yet more cute bunny rabbits. It was signed ‘Eileen Soper’.

In all honesty, despite wafting around in a velvet scarf claiming to be a vintage enthusiast, I had never heard of Eileen Soper. I am ashamed to say I’d nearly ditched the dish at the auction room because (a) I wrongly assumed it was a stand (b) I hadn’t brought enough bubble wrap to package it and (c) my hubby’s shed is so full of vintage ephemera (junk) and he’s threatening to report me to the council as a hoarder.

Eileen Soper turned out to be the Eileen Soper – wildlife artist and illustrator of many Enid Blyton’s books including all of the Famous Five series.

Crumbs….it was almost as exciting as stumbling on a secret underground passage. The more I dug around for information about this wonderful artist, I realised she had a fascinating, somewhat eccentric life to rival any fictional character.

Which is why it’s high time we paid homage to this incredible artist by revealing ten facts about her life.

- She was a child prodigy

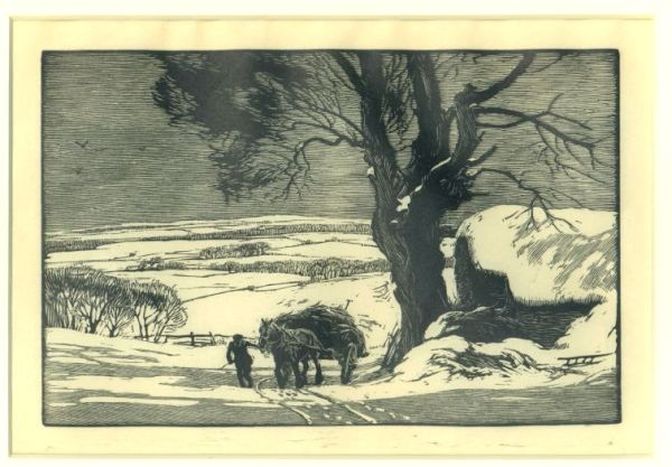

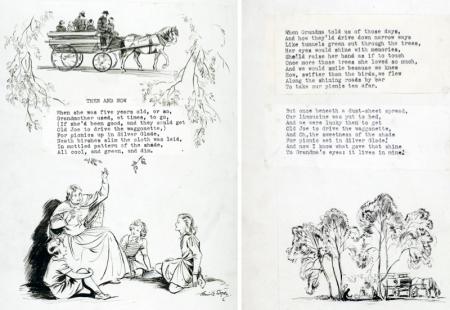

Eileen Soper was the off-spring of accomplished artist George Soper. Under his tutelage, Eileen showed prodigious talent from an early age. Eileen was the youngest exhibitor at the Royal Academy in London. She displayed two etchings of children at play. The work created intense interest and the comment from the jury that ‘Miss Soper, aged fifteen, can hold her own with giants.’.”

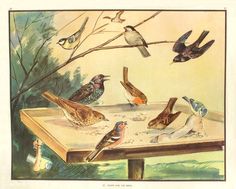

2. She had a talented sibling

Eva Soper became a skilled potter contributing many designs for Royal Worcester. Eva and Eileen studied wildlife in the ‘sanctuary’ garden in Hertfordshire created by their father. When Eva was introduced to the Royal Worcester factory by fine art publisher Alex Dickens, she delighted the home market by designing and modelling a series of twelve British birds she saw regularly around her home. These designs remained in production until 1986. Look out for the Royal Worcester mark, usually in black, and gloss colouring which means it’s an early pre-1950 figure.

3. She was popular with the queen

Throughout her teens and into her twenties, Eileen continued to work alongside her father. During this early period, Eileen produced 180 etchings; most featuring the same group of children – all enjoying simple past-times and games. These ‘fictional’ children were so popular, Queen Mary purchased ‘Flying Swings’ for £4 14s 6d. Critics praised her ability to bring life and movement to her figures – a quality which makes them highly collectible to this day.

Chris Beetles Gallery of London has managed sales of artwork from the Soper estate since 1987. The Fair (pictured above) is available for £450; it is a signed etching and all proceeds go to the The Artists General Benevolent Institution (AGBI).

4. She was inspired by her father’s garden.

When Eileen was three, George and his wife Ada moved with their daughters to Harmer Green, Welwyn, into a house he’d designed. An amateur botanist, George grew many exotic plants in his Hertfordshire garden which spread over four acres. Naturally, the garden provided inspiration for George and his daughters. In the inter-war years, George and Eileen spent many hours together in the garden, painting in both oil and watercolours.

When George died, in 1942 (Ada passed away in 1956) the sisters continued to live in the house, growing old together. Due to failing health both had to go into hospital and then a nursing home. Eileen agreed to up-grade the house to enable her to return home – but died before this was possible. She was 81. Eva was said to blossom after so long in her sister’s shadow. Sadly, she also died in 1990.

After his death, Eileen christened the house Wildings in recognition of her father’s love of nature.

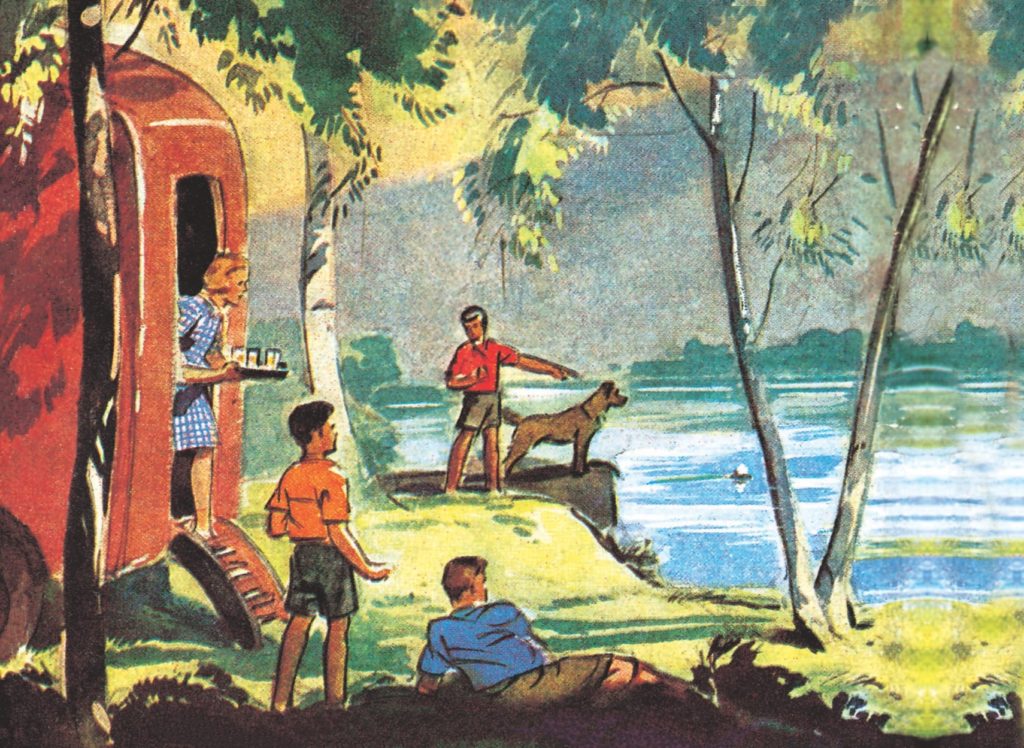

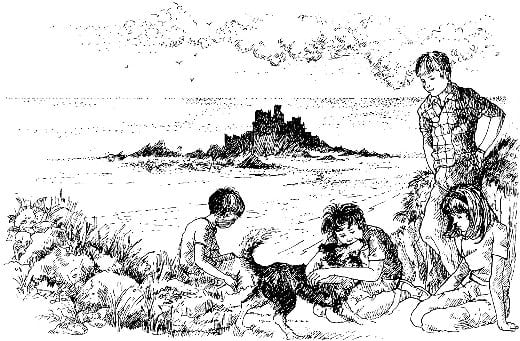

5. She had long association with Enid Blyton

Eileen Soper’s career as a book illustrator began in 1941 when publishers Macmillan suggested her name to Enid Blyton.

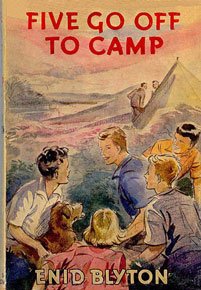

Originally for the nature series, Enid Blyton became a champion of Soper’s work and insisted on her friend being commissioned to illustrate Five on a Treasure Island.

Eileen Soper went on to illustrate 35 books for Blyton over the course of a 25 year long collaboration. But the pair only met a few times. Eileen’s friends reported that she found illustrating for Blyton ‘a chore’ not least because the finickity author often insisted on ‘“footling changes in drawings that were already adequate’.

But in many ways it was a perfect partnership – according to one of her publishers, the formidable Blyton would often stipulate that Soper must be used as her illustrator.

In 1950, Enid Blyton wrote to Eileen Soper enthusing about the artwork for Five Go off to Camp: `I have praised your illustrations, end-papers and jackets most fulsomely to Hodder and have said how lucky it was that we hit on you at the beginning for this series, because a good artist really does help to `make’ the series’.’

In 1950, Enid Blyton wrote to Eileen Soper enthusing about the artwork for Five Go off to Camp: `I have praised your illustrations, end-papers and jackets most fulsomely to Hodder and have said how lucky it was that we hit on you at the beginning for this series, because a good artist really does help to `make’ the series’.’

Last year, in the Guardian, contemporary Blyton illustrator Alex T Smith took readers on a pictorial history of Enid Blyton’s book covers.

He said; ‘I often think that one of the reasons that Enid Blyton’s books are still so popular nowadays is that the children are allowed to go exploring and have adventures by themselves, and this is brilliantly represented by Eileen Soper.’

6. She may have harboured a life-long love for a famous Olympian

When Eileen Soper died, family friend Robert Gilmore, then President of the Society of Wildlife Artists, was one of the people entrusted with sorting out the long neglected family home. He wrote fondly about the chaos which greeted him on entering Eileen’s studio.

‘As with her garden, Eileen had long ago lost control of this large room. Unable to throw anything away, every part was silted up with piles and heaps of paper, boxes, old mounts and overflowing cabinets and chests.’

On a great mahogany studio easel, in the middle of this space, he found ‘Eileen’s enigmatic portrait in oils of Eric Liddell.’

The discovery of this portrait fuelled rumours that Eileen carried a lifelong torch for the Scottish Olympian immortalised in the movie Chariot of Fire.

‘The pair were just teenagers when they first met through a mutual acquaintance,’ recalled Liddell’s biographer Duncan Hamilton in the Daily Record.

‘Eric was boarding at Eltham College in south London and would go down to visit Eileen, her father and sister in their Hertfordshire home. In 1925, a year after his Olympic triumph, Eileen persuaded Eric to postpone his move to China to become a missionary for a few weeks so she could paint his portrait. She painted him as she saw him: – handsome, wise and with a virtuous gleam.’

Eileen had no intention of parting with her keepsake. In fact, there’s evidence to suggest the painting remained untouched on it’s easel for 60 years. As for Eric Liddell, he became a missionary in China. He married a Canadian nurse in 1934 but, at the start of the war, he was placed in an internment camp where he died of a brain tumour in 1945. He was not destined to see Eileen again – and it’s safe to assume he’d forgotten their brief friendship.

Not so Eileen.

Duncan Hamilton thinks one of her many poems holds a vital clue as to her enduring feelings.

‘Only one poem expressed love for a man,’ he says.

‘Entitled ‘To E.L.’ it describes how they walked in the hills and how he etched their initials in a lichen-covered tree trunk with a silver key…Eric must have had feelings for her as he was known for being the least vain man on the planet and posing for a portrait was not in his nature.’

7. She became increasingly reclusive with the passing years

When Eileen’s family moved to Hertfordshire, her father’s was intent on creating a magical garden replete with ferns and bamboos. However idyllic, it was an environment the girls would find it difficult to escape. The girl’s over-protective father and mentor created a benign ‘gilded cage’. Male visitors were discouraged and George was reluctant to let his girls leave the family home.

After their parents death, these childhood habits could not be broken. The sisters retreated from the outside world and the house and glorious gardens became ever more ramshackle. When both both sisters were taken into a nursing home, friends and advisers were finally allowed to enter a house which had been jealously guarded by the women for years.

According to the Sunday Herald;-

‘It was impossible to move. The rooms were crammed with the accumulations of the family’s life. They had kept everything: papers, letters, lawnmower repair bills from 70 years before, 3000 jam jars – kept so that they should not have been thrown on a rubbish dump and thus constitute a risk for badgers cutting their paws – and paintings, sketches and etchings, thousands of them.’

London gallery owner Chris Beetles, a specialist in illustrations, was entrusted to handle the estate which included an amazing amount of artwork. He described the house and garden as ‘Something out of Sleeping Beauty.’

8. She was terrified of germs

One of the less fortunate lessons Eileen and Ava learned from their father George was a fear of infection. Cancer was the ‘dread disease’ which could not be talked about by name. The sisters were convinced cancer was contagious so they avoided public places and were reluctant to receive visitors. When a cousin suffering from cancer wrote to the pair – they handled the letter with tongs and burned the doormat on which the letter had fallen. Tea was boiled for twenty minutes to kills the germs – and yet they allowed the local wildlife eat from their hands and birds flew freely around the house.

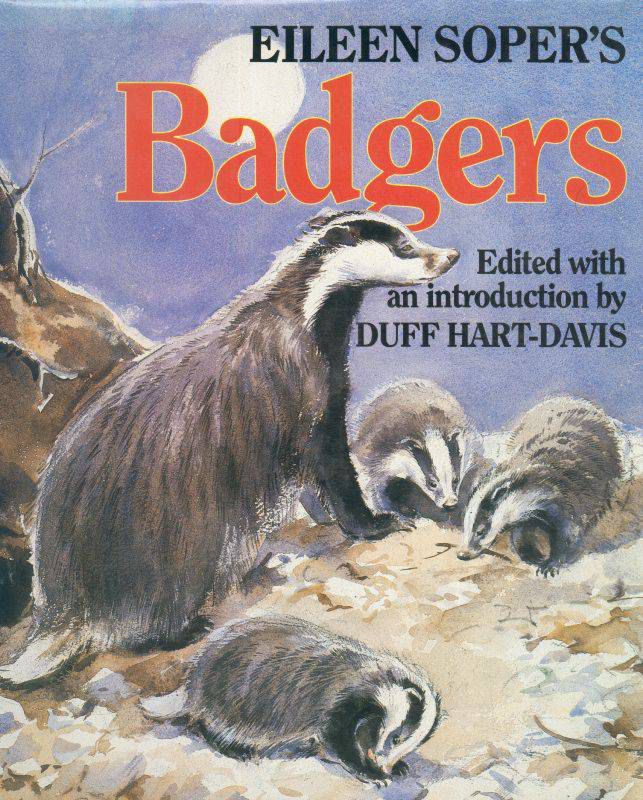

The lonely existence allowed the women to cultivate an extraordinary relationship with the surrounding wildlife. Eileen produced a book about badgers based on 500 hours of personal observation. We know a lot about these years because Eileen conducted a number of friendships by mail.

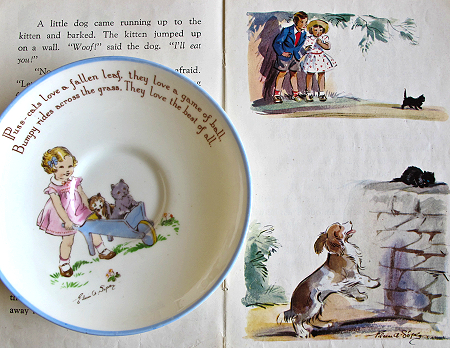

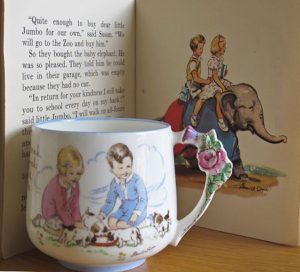

9. She designed a range of pottery for Paragon China

Barbara Fisher, who runs the popular blog March of Time Books, is an avid collector of Eileen Soper’s nursery ware and has written several articles about the designs including The Playtime series produced in the 1930s.

‘Eileen Soper is perhaps not so well known as a designer of nursery ware,’ she says.

‘But I love the pretty designs. A plate from the Playtime series was my most inexpensive purchase to date – spotted for just £9 in a charity shop. It has a small hairline crack, hence the price. The handles on the cups are incredibly delicate and not really designed for little hands, and that’s probably why I collect them.’

Many of the nursery pieces feature illustrations Eileen had completed for Enid Blyton – and included lines of verse including ‘all puppies love their milk to drink’.

Expect to pay from £19 for an undamaged saucer. A bowl for £25 (source: private sales recorded on eBay).

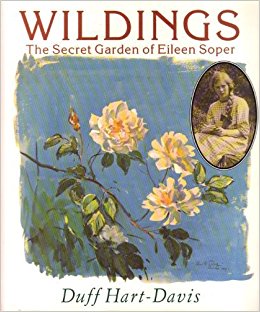

10. She inspired a beautiful collection of reminiscences

Wildings; The Secret Garden of Eileen Soper by Duff Hart-Davies documents the fascinating family history and features many of her exquisite paintings and drawings. The book was based on discoveries in the treasure trove that was Wildings after Eileen passed way. The collection included more than 200 watercolours by Eileen herself, as well as a very large number of her drawings, sketchbooks and letters.

Now out of print, Amazon has copies available from £2.80.

To buy artwork by Eileen Soper, visit the Chris Beetles Gallery

Sources

Daily Record; Revealed; Enid Blyton artist’s secret love for Chariots of Fire Legend Eric Liddell

Eva Soper’s Birds, Museum of Royal Worcester

Stella & Rose’s Books Eileen Soper

Suffolk Painters: George Soper

Andrew Graham-Dixon: Eric Liddell by Eileen Soper

My little dish is listed for sale on Etsy