Buying knick-knacks antiques at auction can be a frustrating experience. Unless the haul comes with authenticated provenance, you’re often bidding for an anonymous item wrapped in a 15-year-old copy of the Sun and dumped in a banana box.

Former owner(s) unknown.

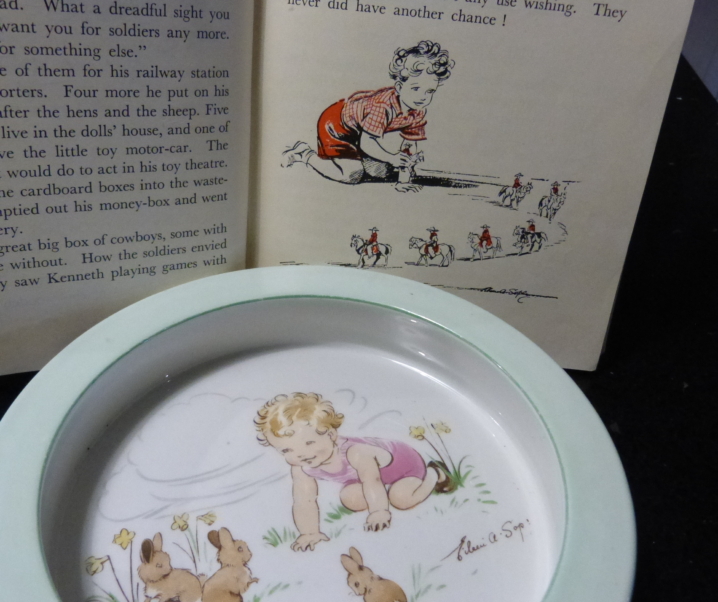

I wish the trio of 1930s treasures I found at a sale room in Bakewell could talk. They were all elegant dressing table decorations circa 1930; an age when ladies retired to their ‘boudoir’. They oozed quality. The porcelain half-doll was dressed in an outrageously ruffled skirt which concealed a lavender holder – still fragranced. The other doll was a tiny ‘snowflake’ ballerina designed to sit on a powder compact. The third was a remarkably intact mirror framed by perfectly preserved paste flowers.

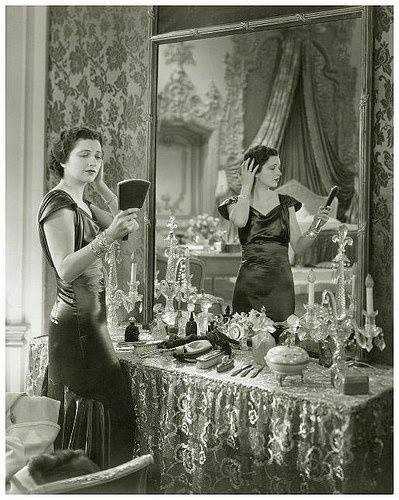

Looking at the little mirror, my mind was flooded with an image of the society beauty who might have owned it. I could almost see her at a skirted dressing table performing the last stage of her toilette – puffing Yardley ‘lavende’ behind the ears, taking a final sip of martini before applying cherry red lip stick in the flower-decked mirror and dashing off to dance. For reasons I cannot explain, this lady is called Doris.

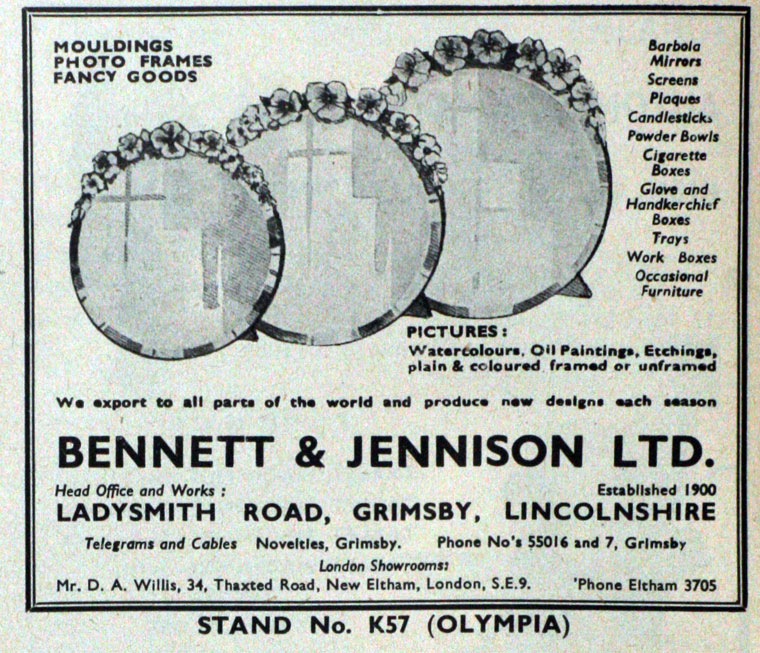

The only hard fact I have about the mirror is its name. Barbola. There’s also an unexpected link between this fashionable item and the unfashionable place of my birth – Grimsby.

Here’s half a dozen hard facts I know about Barbola mirrors. Sadly, what happened to the woman in the mirror – Doris or otherwise – is lost in the midsts of time.

They are called Barbolas but this refers to the frame and not the mirror

Barbola is gesso work decoration common to lots of items including fire screens, trinket boxes and cigarette holders. According to Lidy Baars of French Garden House, gesso paste was used as a lighter, cheaper substitute for carved wood.

‘Carving was labour intensive and costly, it was also very heavy,’ Lidy explains in an article on Barbolas for eBay.

‘Gesso is a paste made by mixing whiting with size or glue to a mouldable consistency, which will dry hard. It’s a very old form of decoration.”

Barbola mirrors were hugely popular in England at the turn of the last century but – with the delicate flowers being susceptible to damage – they are relatively scarce and highly collectible. They are especially prized in America where prices can exceed $100 (£72).

They were made in Grimsby

The name ‘gesso’ implies Italian origins and the fashionable set would undoubtedly buy a lot of their ornate moulded trinkets and furniture from the continent.

But, here’s a thing. Advertisements show Grimsby-based firm Bennett and Jennison Ltd were making a good living from Barbola mirrors along with other fancy picture frames. Solomon Bennett was listed in the 1911 census as a picture frame manufacturer. Born in born in Russia, Solomon lived at 82 Cleethorpes Road and was father to five children – two of whom were engaged in the business. Jennison was the manager of the manufacturing side of the business and their output included fire screens and cigarette boxes. It was a profitable business, when Jennison died in Cleethorpes in 1949 his estate valued more than £17,000 (around half a million).

They were sold in DIY kits

According to antique expert Lidy Baars, in the 1920s the art supplies firm Windsor and Newton began to sell home kits to young ladies of ‘good birth’ (think Doris and her pals) allowing them to make a hand crafted gift for their own boudoir or that of a suitably well-born friend or relative.

The modelling kit would contain paste (gesso) glue, paints, brushes and modelling tools. The kit contained a booklet of instructions showing how to make the different types of flowers including roses, anemones and poppies. The individual flowers would be hand-painted, glued onto the mirror – or trinket box – and then varnished.

Lidy believes the paints supplied with these kits give modern day purchasers a way of dating Barbola mirrors. The fashion at the time was for strong, rich shades of blues, greens, umbers and reds. If the flowers on a Barbola you find are pastel shades then you can assume the flowers are re-painted, replaced or that the whole piece was made at a later date.

“That is not to say they are without value,” Lidy says of the re-painted pieces.

“Many of these pieces are highly sought after for their beauty, they are also quite collectible.”

They are often damaged goods

The hardened gesso was highly susceptible to damage – even changes in the weather would crack the paste. If your Barbola is from the 1930s the it is likely to have superficial cracks, chips and even bits missing.

Unless it’s held together with glue and staples, your Barbola will not lose value even if it’s in a shabby condition. Lidy Baars, an antique dealer, says she has never seen an early example without some wear/damage.

They are HIGHLY collectible

They are HIGHLY collectible

Designer Pam Balla is just one admirer. Pam documents the transformation of her Californian Cottage on the popular blog White Ironstone Cottage.

Her gorgeous dining room features many salvaged and pain-stakingly sourced items but her favourite is – her Barbola mirror.

“I love to imagine the lovely Victorian women who received this mirror brand new,” she says.

Fellow enthusiast is furniture up-cycler Emma Kate of Paint and Style Blog. Emma has been collecting them for years (see above).

“None of my Barbolas cost very much. Even the large one was under a tenner,” she says.

“I had to remove some stands from the backs as they are often designed to sit atop a dressing table. When you take them apart you can sometimes find dates inside. Most date from the twenties to the forties.”

They are very saleable

You can pay around £15 – £25 for the Barbolas which have been crudely painted by ‘lady’ crafters (sorry Doris). While researching this piece, I have seen vintage pieces for sale for £25-plus. Well-preserved items sell for £50-upwards. Barbolas are still made today so beware of falling in love with an old-looking fake. Individual flowers, cracking and the frame/easel are all indications you have a genuine antique mirror.

Information on Bennett and Jennison can be found at Grace’s guide to British Industrial History